A Three-Wave Model for the Peopling of the Americas, or a Three-Wave Back-Migration from the Americas to the Old World

Nature (2012) doi:10.1038/nature11258

Reconstructing Native American population history

Reich, David, et al.

The peopling of the Americas has been the subject of extensive genetic, archaeological and linguistic research; however, central questions remain unresolved. One contentious issue is whether the settlement occurred by means of a single migration or multiple streams of migration from Siberia. The pattern of dispersals within the Americas is also poorly understood. To address these questions at a higher resolution than was previously possible, we assembled data from 52 Native American and 17 Siberian groups genotyped at 364,470 single nucleotide polymorphisms. Here we show that Native Americans descend from at least three streams of Asian gene flow. Most descend entirely from a single ancestral population that we call ‘First American’. However, speakers of Eskimo–Aleut languages from the Arctic inherit almost half their ancestry from a second stream of Asian gene flow, and the Na-Dene-speaking Chipewyan from Canada inherit roughly one-tenth of their ancestry from a third stream. We show that the initial peopling followed a southward expansion facilitated by the coast, with sequential population splits and little gene flow after divergence, especially in South America. A major exception is in Chibchan speakers on both sides of the Panama isthmus, who have ancestry from both North and South America.

Reich et al. (2012) claim to have provided the “most comprehensive survey of genetic diversity in Native Americans so far” (p. 4). This led them to revive the three-wave theory of the peopling of the Americas famously advanced by the linguist Greenberg, odontologist Turner and geneticist Zegura in the late 1980s but refuted by a host of genetic and linguistic publications ever since. This doesn’t make the three-migration model for the peopling of the New World automatically wrong, of course, but it does make one uncomfortable with the ever-volatile results of population genetic studies and skeptical about the chances that this new genetics paper will be able to find support among linguists. However, as I will try to show below, a reinterpretation of Reich et al.’s data in light of out-of-America thinking creates a perfect fit between genetics and linguistics.

From the very start, Reich et al. (2012) show their ignorance of the state of American Indian linguistic classifications. They write,

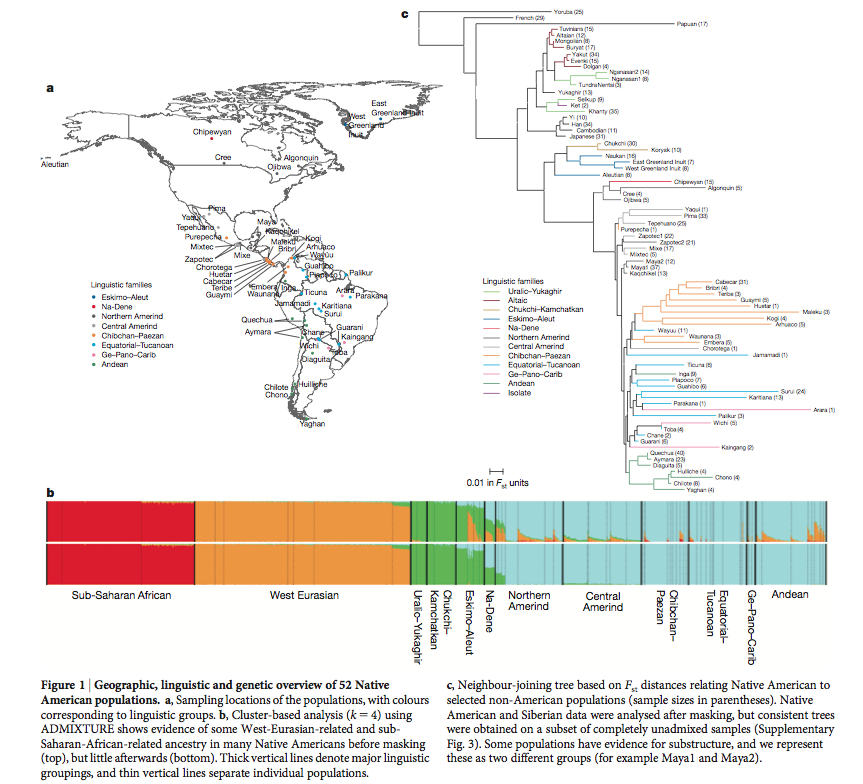

“We built a tree (Fig. 1c) using Fst distances between pairs of populations, which broadly agrees with geography and linguistic categories.”

Fig. 1 operates with such “language categories” and “major linguistic groupings” as “Northern Amerind,” “Central Amerind,” “Ge-Pano-Carib,” which are not supported by mainstream American Indian linguistics. And they reference Ruhlen, M. A Guide to the World’s Languages. Stanford, 1991. Although Ruhlen’s Guide is a useful compilation of information about world’s languages, Greenberg-Ruhlen’s classification of American Indian languages into three phyla – Amerind, Na-Dene and Eskimo-Aleut -, as well as his subgrouping ideas for Amerind, are universally rejected. Reich’s “major linguistic groupings” are therefore no more real than, say, “macrohaplogroup U-D” in mtDNA genetics.

It’s noteworthy that in their ADMIXTURE plot the American Indian (“First American”) component is present across all Greenbergian linguistic phyla and even extends to Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Uralo-Yukaghir (both of them Greenberg classified as “Eurasiatic,” again without much acceptance) and, most importantly, into “West Eurasian” populations. Alternatively, the “Siberian” component found in Chukchi-Kamchatkan and Uralo-Yukaghir doesn’t extend beyond Na-Dene in the New World casting doubt on the recent “Asian” origin of American Indians. The Fst-based tree by Reich et al., then, must reflect geography, rather than history, as the Yoruba, Papuans, Japanese, Chukchis are simply progressively closer to American Indians geographically but don’t necessarily mean that the branching order reflects population movement from Africa through Asia to the Americas.

A closer look at the ADMIXTURE plot reveals that the Amerindian component is also found among “West Eurasian” populations (at similar levels as the “Chukchi-Kamchatkan-Uralo-Yukaghir” component), while the “West Eurasian” component is found next to the Amerindian and the Chukchi-Kamchatkan-Uralo-Yukaghir components in Sub-Saharan Africa. So, there’s snowball effect linking the New World, the New World and Siberia, the New World, Siberia and West Eurasia back to Sub-Saharan Africa. This is consistent with most other ADMIXTURE runs conducted by academics and genome bloggers alike and supports an out-of-America model of human dispersals. Apparently, the presence of an “eastern” component in northern Europeans creates a spurious effect of African admixture in southern Europe. Had Reich et al. used the widely-accepted classification of American Indian languages into 140 language stocks (Campbell, Lyle. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford, 1997) they would have noticed that the highest concentration of the Amerindian component is associated with 2/3 of world language diversity, with the progressive decline of this component as one crosses the Bering Strait back into the Old World.

In 2004, linguists published a letter to the editor of The American Journal of Human Genetics issuing a plea to geneticists to “cease and desist” the use of the Greenbergian classification of American Indian languages in population genetic research because of its egregious flaws. Reich et al. (2012) ignored the request probably hoping that population genetics is more powerful than linguistics and can guide linguists to “better” classifications. But by doing so, they also run counter to a large number of publications by fellow geneticists showing that all American Indians derive from one single founding migration.

But there is no need for linguists to go toe-to-toe with linguists. Reich’s own data offers a much more elegant solution to the puzzle of the origin of American Indian genetic and linguistic diversity. They write (p. 4),

“We also arrive at the finding that Eskimo–Aleut populations and the Chipewyan derive large proportions of their genomes from First American ancestors: an estimated 57% for Eskimo–Aleut speakers, and 90% in the Chipewyan, probably reflecting major admixture events of the two later streams of Asian migration with the First Americans that they encountered after they arrived. The high proportion of First American ancestry explains why Eskimo–Aleut and Chipewyan populations cluster with First Americans in trees like that in Fig. 1c despite having some of their ancestry from later streams of Asian migration, and explains the observation of some genetic variants that are shared by all Native Americans but are absent elsewhere”

It’s much more parsimonious to interpret this massive sharing of the Amerindian (“First American”) component by Eskimo-Aleuts and Na-Dene populations as evidence of shared origin of all three groups from this Amerindian component, not as varying degrees of admixture derived from three different waves of migration to the New World. This will be consistent with grammatical-linguistic evidence attesting to the uniqueness of all New World languages (Eskimo-Aleut, Na-Dene and the rest) compared with Old World languages.

The genetic implication of this very simple logic is that the “Siberian” (Chukchi-Kamchatkan-Uralo-Yukaghir) component is derived from the New World. This is consistent with Reich et al. (2012) finding of evidence for a

“back-migration of populations related to the Eskimo–Aleut from America into far-northeastern Siberia (we obtain an excellent fit to the data when we model the Naukan and coastal Chukchi as mixtures of groups related to the Greenland Inuit and Asians). This explains previous findings of pan-American alleles also in far-northeastern Siberia.”

The hypothesis of a large-scale migration from the New World to Siberia removes the triple logical contradiction that exists between Reich et al.’s “finding” of gene flow of Asians to Eskimo-Aleuts and, simultaneously, of gene flow from Eskimo-Aleuts to Asians carrying “pan-American” alleles that Eskimo-Aleuts had absorbed from “First Americans.”

The authors admit another hidden logic behind the data. In the Supplemental Material (pp. 11-12) they write,

“A complication in computing this statistic is that Native American, Siberian, and East Asian populations are not all equally genetically related to West Eurasian populations, as we can see empirically from 4 Population Tests of the proposed tree (Yoruba, (French, (East Asian, Native American))) failing dramatically whether the East Asian population is Han, Chukchi, Naukan and Koryak. The explanation for this is outside the scope of this study (it has to do with admixture events in Europe, as we explain in another paper in submission). In practice, however, it means that we cannot simply use a European population like French to represent West Eurasians in Equation S3.2, since if we do this, Equation S3.2 may have a non-zero value for a Native American population, even without recent European admixture.

To address this complication, we took advantage of the fact that east/central Asian admixture has affected northern Europeans to a greater extent than Sardinians (in our separate manuscript in submission, we show that this is a result of the different amounts of central/east Asian-related gene flow into these groups). To quantify this, we computed the statistic f4(San, West Eurasian; Pop1, Pop2) for West Eurasian = Sardinian and West Eurasian = French, and for 24 Siberian and Native American populations (Pop1 and Pop2) (Figure S3.2). Figure S3.2 shows a scatterplot for all 190=20×19/2 possible pairs of these populations. Within non- Arctic Native populations, and within Arctic populations (East Greenland Inuit, Chukchi, Naukan and Koryak), the statistics are close to zero, consistent with their being (approximate) clades relative to West Eurasians. In contrast, there are deviations from zero when the comparisons are between non-Arctic Native and Arctic populations, with non-Arctic Native populations showing consistent evidence of being genetically closer to West Eurasians.”

This means that the West Eurasian component seen in the New World part of the ADMIXTURE plot doesn’t all come from recent admixture but may in fact represent an ancient connection between American Indians and West Eurasians, which is not shared by Siberians. This is consistent with mtDNA studies that show that non-Arctic North American Indians possess hg X related to hg X found in Europe and the Middle East, but not found in Siberia. But Siberians share their “green” component with American Indians to the exclusion of West Eurasians. Again, this is consistent with mtDNA studies. So, what in fact we see is not just an Arctic Siberian-Eskimo-Aleut nexus, a Sub-Arctic-Siberian-Na-Dene nexus but also a non-Artic American Indian-West Eurasian nexus. Since the Amerindian component is found all across Eurasia, it’s most parsimonious to interpret these multiple connections between Old World and New World populations as an ancient population expansion from the New World to the Old World.

I’ve read that early migration movement was either 10 miles per generation or 100 miles per generation. Either way, where do those speculative figures come from? What scientific evidence would support either? I “Hike Apacheria” and have studied for a decade where the Apache were, using anecdotal information from Apache sources, but also, primarily, military records or other historical records. The records contained in the National Archives, whether the former or latter, as well as Bureau of Indian Affairs documents, often give fairly precise mileage distances the military traveled through “Indian country.” Not sure how they were confident of their estimates, but using such records, & a combination of then current maps (U.S., 1850-1890), current maps, landmarks, names of places (historical & no longer used or names that have transcended time), I’ve found battle sites, possible rancheria, etc.

I assume that the earlier figures mentioned above were for humans walking exclusively. Obviously, by the time peoples in the Americas obtained horses, they were able to migrate much greater distances.

However, it would be instructive to know how many generations of WALKERS it took to cross the Beringa Strait & walk into the area around CLOVIS, NM. Does anyone have any information on this?