2There are several possible hypotheses that model the origin of Old World populations from the New World:

I. Out-of-America, with human origins from New World primates. This idea was first put forth by the Argentinian anthropologist and paleobiologist, Florentino Ameghino (1854-1911). Below one can see Ameghino’s version of a primate phylogeny in which hominin species found as fossils in the Old World, as well as living Homo sapiens, are derived as subtending from a Platyrrhine tree.

From: Ameghino, F. 1909. “Le Diprothomo platensis, un precurseur de l’homme du pliocene inferieur de Buenos Aires,” Anales del Museo Nacionalde Historia Natural de Buenos Aires. 1909. 19. Pp. 107-209; Hrdlicka, 1912. A. Early Man in South America. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; Politis G., Barrientos G., Stafford T. W. 2011. “Revisiting Ameghino: New 14C Dates from Ancient Human Skeletons from the Argentine Pampas,” in Peuplements et Préhistoire en Amériques. Paris. P. 45.

Ameghino inverted the nascent 19th century evolutionary logic of species formation and proposed that Old World apes and hominids such as Neandertals were bestialized forms of the early small, bipedal American man named Homunculus. After the separation of those bestialized lines from the Homo lineage the ancestral Homo population split into Homo sapiens (ancestor of American Indians and Caucasians) and Homo ater (ancestor of Africans and Australians) (Podgorny, Irina. “Human Origins in the New World? Florentino Ameghino and the Emergence of Prehistoric Archaeology in the Americas (1875–1912).” PaleoAmerica: A journal of early human migration and dispersal 1 (2015): 74). Ameghino infused his paleontological work with both Argentinian nationalist and Judeo-Christian sensibilities (comp. Ezekiel 37:1-14) as the following illustrious quote from his presentation at the International Scientific Congress in Buenos Aires in 1910 (at the centennial of the onset of the secessionist civil war in Argentina) illustrates:

“It seems as if the ancient and now extinct species and races of man that inhabited our land have awoken from ultra tumba, in order to attend, even though only with their inanimate bones, the celebration of our centennial” (Ameghino, Florentino. “Descubrimiento de un esqueleto humano fósil en el pampeano superior del Arroyo Siasgo.” In Congreso Científico Internacional Americano. Buenos Aires, 1910; quoted in Podgorny 2015: 74).

Dismissed by Ales Hrdlicka and the rest of the scientific community, the New World primate (Platyrrhine) origin of modern humans is now championed by Alvah Hicks, a California-based self-taught anthropologist and a one-time member of the Mother Tongue group. He was profiled in the Los Angeles Times in 1993. Out-of-America I has no fossil evidence to support it. This may not be the most serious argument against it because, up until 2003 science was unaware of Homo floresiensis; prior to 2005, it didn’t have any fossil remains of African apes (and it still has no gorilla fossils); and up until 2010 it had no idea of the existence of the Denisovan hominin. The latter case is particularly instructive as the identification of a new hominin species from Northeast Asia was enabled by new ancient DNA extraction technologies, the initial fossil material (tooth and phalange) being utterly minimal and opaque. The primate fossil record in the New World remains notoriously poor compared with other mammals:

“Considering the extensive living radiation in the Neotropics today and the relatively good fossil record for other South American mammals, the fossil record of New World monkeys is relatively poor. Until recently, a large show box could contain the primate fossils from all of South America and the Caribbean from the last 30 million years.” (Fleagle, John G., and Richard F. Kay. “Platyrrhines, Catarrhines, and the Fossil Record,” in New World Primates: Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, edited by Warren G. Kinzey. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, p. 3).

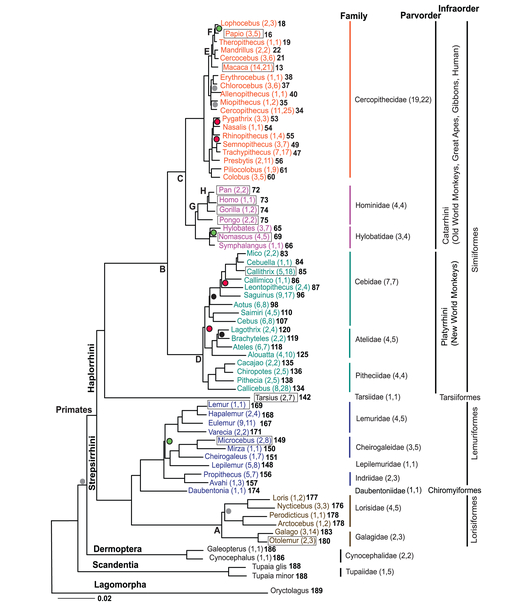

More importantly, out-of-America I runs into a host of insurmountable biological problems such as the presence of a range of synapomorphies between humans and great apes (e.g., two premolars in Old World monkeys, apes and humans vs. three premolars in New World monkeys; opposable thumb in apes and humans vs. non-opposable thumbs in marmosets and pseudo-opposable thumbs in Cebidae). It’s also contradicted by primate gene phylogenies, which place humans squarely with Hominidae in a sister clade with Pan (see below, from Perelman et al. “A Molecular Phylogeny of Living Primates,” PLoS Genetics 7 (3), 2011).

For out-of-America I to be correct, all the genetic and biological similarities between Hominidae, Hylobatidae and Cercopithecidae need to be reinterpreted, very implausibly, as homoplasies or products of convergent evolution. At the same time, under a closer inspection, some of these physical traits can be polymorphic in New World primates: for instance, trichromacy is fixed in Catarrhines – the parvorder comprising Old World monkeys (Cercopithecines), apes and humans – but is polymorphic in New World primates, so that howler monkey matches Catarrhines in having trichromatic color vision. The Late Pleistocene fossil monkey Paralouatta varonai from Cuba shows the surprising presence of semi-terrestrial skeletal features (all living Platyrrhines are almost exclusively arboreal), supraorbital torus and low vault (these traits are co-present in Homo erectus and Neandertals) as well as an incipient chin suggesting a unique evolutionary path different from the other Platyrrhines (McPhee, R. D. E., and Jeff Meldrum. 2006. Postcranial Remains of the Extinct Monkeys of the Greater Antilles, with Evidence for Semiterrestriality in Paralouatta. New York: American Museum of Natural History).

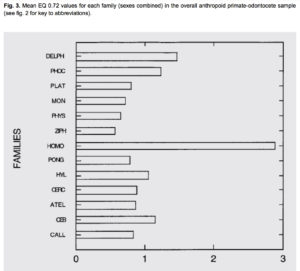

Cebidae have larger brains, compared to their bodies, than great apes (see encephalization indices across a number of animal families below, from: Marino, L. “A Comparison of Encephalization between Odontocete Cetaceans and Anthropoid Primates.” In Brain, Behavior and Evolution, 1998); PONG are Pongidae, CEB are Cebidae).

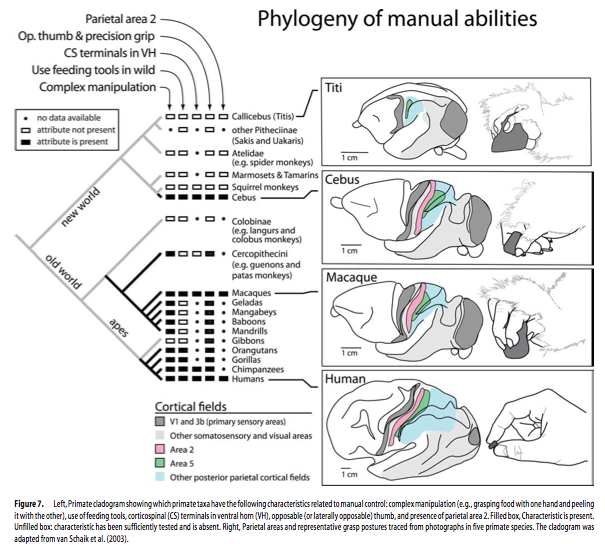

Cebidae are unique among Platyrrhines in having all the neural and physical components of superior manual control (including precision grip achieved through pseudo-opposable thumbs) otherwise found only in macaques and humans. Even chimpanzees may not be as dexterous as Cebus (see below, from Padberg, Jeffrey, et al. “Parallel Evolution of Cortical Areas Involved in Skilled Hand Use,” Journal of Neuroscience 27 (38): 10106-10115).

Correspondingly, wild capuchins have been recently shown to manufacture hominin-grade stone tools, which again sets them apart from great apes and makes them closer to humans. Just like humans, they are omnivorous, practice extracting foraging, are tolerant to each other during foraging and even sometimes share food (Perry, S. 2003).

The plot further thickens when we discover that New World monkeys, just like bonobos and humans, have non-conceptive sex across any age-sex combinations (Manson, Joseph H., Susan E. Perry, and Amy R. Parish. “Nonconceptive sexual behavior in bonobos and capuchins.” International Journal of Primatology 18 (1997): 767–86). Wild capuchins have a relatively large frequency of same-sex and adult-immature sexual encounters. But what sets New World monkeys apart from any great apes is pronounced forms of pair bonding (a stable monogamic reproductive unit), paternal investment in offspring and cooperative breeding (a social system whereby infant care behaviors are exhibited by all group members, not just the biological mother of the infant). As an example, below is the distribution of conspicuous paternal care across primate branches (from: Fernandez-Duque, Eduardo, Claudia R. Valeggia, and Sally P. Mendoza. 2009. The Biology of Paternal Care in Human and Nonhuman Primates. Annual Review of Anthropology 38: 115-130.)

As it can be observed, siamangs is the only Old World primate species that has conspicuous paternal care. Otherwise, modern humans and New World monkeys are unique in having this trait. The only case of attachment between mammal infant and father, outside of humans, is attested in dusky titi monkey (Callicebus moloch) (Hoffman, K. A., S. P. Mendoza, M. B. Hennesey, and W. A. Mason. 1995. “Responses of Infant Titi Monkeys, Callicebus moloch, to Removal of One or Both Parents: Evidence for Paternal Attachment,” Developmental Psychobiology 28 (7): 399-407).

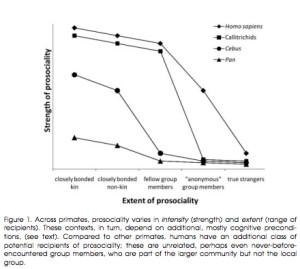

Studies of both captive and wild primates have consistently returned one observation: in the degree and strength of prosociality, New World Callitrichids are the closest to modern humans, while African apes trail behind (see below, Fig. 1, from Burkart, Judith M., Sarah B. Hrdy, and Carel P. Van Schaik. “Cooperative Breeding and Human Cognitive Evolution.” Evolutionary Anthropology 18 (2009): 178). Callitrichids and humans are unique among primates in showing prosocial behaviors (e.g., food sharing) toward unrelated individuals and often at a cost to oneself.

Burkart et al. (2009, 178) summarize the pattern seen in Fig. 1 in the following way:

“Indeed, callitrichid society is characterized by strong social bonds among all group members. Privileged relationships within specific dyads are rare and hard to detect. In contrast, in both chimpanzees and capuchin monkeys, altruistic acts are typically limited to close friends and bonded kin or depend on dominance. Experimental evidence regarding these monkeys is drawn from preselected subjects for which it was known in advance that they would be particularly prone to pay attention to a partner or that had been successful in cooperating in previous tests. Moreover, the strength of prosociality is strongest in callitrichids. In food contexts, common marmosets perform altruistic acts even at some cost without deriving a benefit for themselves at all, while capuchin monkeys cease their prosocial behaviors under unequal reward distributions and chimpanzees fail altogether to show altruistic tendencies.”

Pair bonding, paternal investment and cooperative breeding are unknown among the great apes. Levels of body size sexual dimorphism among Australopithecines, an indicator of the intensity of male-male competition and rates of polygyny, are more similar to those of other apes (Plavcan, J. M., C. A. Lockwood, W. H. Kimbel, M. R. Lague, E. H. Harmon. 2005. Sexual Dimorphism in Australopithecus afarensis Revisited: How Strong Is the Case for a Human-like Pattern of Dimorphism? Journal of Human Evolution 48 (3): 313-320). Alternatively, pair bonding, paternal investment and cooperative breeding are central to human kinship and social behavior. The influential book by primatologist Bernard Chapais, Primeval Kinship: How Pair-Bonding Gave Birth to Human Society (2008), defines pair bonding as a threshold separating the promiscuous and male-dominant society of great apes from human society. Pair bonding and cooperative breeding are fundamental to the evolution of prosociality, cognitive development, economic cooperation and reduction of intragroup violence (see more here). As anthropologist Kim Hill put it, “Humans are not special because of their big brains [the trait we supposedly inherited from great apes.-G.D.]. That’s not the reason we can build rocket ships — no individual can. We have rockets because 10,000 individuals cooperate in producing the information.” Pair bonding, paternal investment and cooperative breeding (allomothering) form an interrelated functional whole with a common physiological foundation.

Notably, the most compelling examples of parallels to human speech (high phonetic variation, categorical perception, turn-taking, lexical syntax, metacommunication, babbling, etc.) among primates come not from the great apes but from the New World monkeys. Whereas the vocal repertoire of great apes is impoverished, New World monkeys are extremely vocal, maybe most vocal among all primates (gibbons are a close second). Unlike Old World monkeys, New World monkeys are exclusively arboreal. Dense vegetation of the tropical forest makes visual cues hard to perceive, plus arboreal primates use their limbs for locomotion and gesturing is limited among them. Hence their adaptation necessitates that they rely not so much on visual as on auditory cues. (See an important paper by Charles T. Snowdon “Is Speech Special: Lessons from New World Primates” In New World Primates: Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, edited by Warren G. Kinzey. Pp. 75-93. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1997.) It will be interesting to see the results of the sequencing of FOXP2 gene, which is known to be implicated in language abilities in birds and humans, in Platyrrhines.

As an example of remarkable Platyrrhine-Homo convergence, wild capuchins have been described as a species with “social traditions” (hand-sniffing, sucking of body-parts, games, etc.) (Perry, Susan, et al. “Social Conventions in Wild White-faced Capuchin Monkeys: Evidence for Traditions in a Neotropical Primate.” Current Anthropology 44, no. 2 (2003): 241-68; Perry, Susan. “Social traditions and social learning in capuchin monkeys (Cebus).” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences 366 (2011).)

Another striking parallel to human culture involves duet singing, which achieves high development in such species of New World primates as titi monkeys (Müller, Alexandra E., and Gustl Anzenberger. (2002). “Duetting in the Titi Monkey Callicebus cupreus: Structure, Pair Specificity and Development of Duets,” Folia Primatologica 73 (2-3): 104-115). Although duetting is observed in Old World monkeys (siamangs) and African apes (bonobos), it’s not found in common chimpanzees and in bonobos it doesn’t seem to be as developed as in New World monkeys and siamangs. There are strong reasons to believe that speech and promusical vocalizations in monkeys are ways to reinforce and facilitate pair bonding and allomothering (see, e.g., Matasaka, N.,, and M. Kohda. (1988). “Primate Play Vocalizations and Their Functional Significance,” Folia Primatologica 50 (1-2):152-156; Geissmann, Thomas, and M. Orgeldinger. (2000). “The Relationship Between Duet Songs and Pair Bonds in Siamangs, Hylobates syndactylus, ” Animal Behaviour 60: 805-809). Also, as evolutionary musicologist, Joseph Jordania (Jordania, Joseph. (2009) “Times to Fight and Times to Relax: Singing and Humming at the Beginnings of Human Evolutionary History,” Kadmos 1, 272–277), points out, music is a risky behavior, as predators can easily determine the whereabouts of a singing individual. Consequently, the species known to produce music are either arboreal (birds, New World primates, siamangs) or aquatic (whales, dolphins, sea lions). The same selective constraint would apply to speech, hence it’s not surprising that both music and speech are attested in exclusively arboreal New World monkeys. Humans is the only species that combines speech and music behaviors with terrestrial adaptation.

Judging from the well-established primate phylogeny, manual control, pair bonding, paternal investment, cooperative breeding and their communicative outcomes (speech and duet singing) must be homoplasies between New World primates and humans. Convergent evolution is fairly typical in mammals and primates: elephants resemble humans by having such features as large brains, empathetic social bonds, high intelligence, and prolonged development and long life span, not found among their fellow Afrotherians (Goodman, Morris, et al. “Phylogenomic Analyses Reveal Convergent Patterns of Adaptive Evolution in Elephant and Human Ancestries,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (49): 20825-29); brain size enlargement developed in parallel in stem Catarrhines and stem Platyrrhines; encephalization increased further in great apes, some Old World monkeys and some New World monkeys (Cebus) (see Goodman, Morris, and Kristin N. Sterner. 2010. “Phylogenetic Evidence of Adaptive Evolution in the Ancestry of Humans,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, Suppl. 2: 8918-8923.)

In order to reconcile the deep social and behavioral divide between humans and African apes, researchers have proposed the following evolutionary scenario. Hominins inherited from their LCA with chimps a chimp-like cognitive system capable of “mutual state understanding” but since then (in the course of 8-13 million years that elapsed since the split of chimps and the lineage leading to modern humans) they acquired cooperative breeding that was conducive to spontaneous prosociality. It’s the marriage between mutual state understanding and cooperative breeding that resulted in the development of “shared intentionality,” which is the core of the uniquely human cognitive system. Burkart et al. (2009, 177) depict this process with the help of a diagram that shows the intrusive nature of cooperative breeding that entered an ape lineage as an additive but ultimately revolutionary “ingredient.”

But what if cooperative breeding is plesiomorphic among primates? It’s noteworthy that the earliest Catarrhine fossils in the Old World are essentially Platyrrhine-like in cranial and post-cranial morphology (Fleagle & Kay 1997, 20), which suggests that Platyrrhines are not only diverse but also conservative and, consequently, their “human-like” behavioral features may represent retentions from the last common ancestor (LCA) of Platyrrhines and Catarrhines. Better preserved in some species of New World monkeys, these ancestral features got lost in the Old World among such Hominidae as chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans.

If taken in isolation from the primate molecular phylogeny, this “calculus of humanity” could be viewed as supportive of Out-of-America I. Correspondingly, such aspects of modern African human social organization as high rates of polygyny (especially among farmers) will be homoplastic with great apes and Australopithecines. Do we have the seeds of a major scientific controversy here comparable to the relentless “flying primate” debate in mammalian biology? When DNA supports the megabat-microbat grouping, while brain structures support megabat-primate grouping, science is put into an uncomfortable zone of having to make an “executive decision” because straight facts lead to hung jury. Primate research has been dominated by the “myth of the typical primate” (see Strier K. B. “Myth of the Typical Primate,” Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 37 (1994): 233-271) that obfuscates the biological and behavioral diversity of New World monkeys (they display a full range of primate blood types, forms of locomotion outside of bipedalism, diet, vision, social organization) and forces an idealized ape and an idealized human into the Darwinian “hidden bond of connexion.” As Warren Kinzey (“New World Primate Field Studies: What’s in It for Anthropology,” Annual Review of Anthropology 15 (1986), 137) wrote, “Anthropologists have tended to overlook the New World primates because they are not in the mainstream of hominid evolution.” Ironically, as I pointed out in The Genius of Kinship, this is exactly what happened to the study of American Indian cultures and kinship systems, so we may have here a general pattern of reductionism and bias driven by Old World-centric assumptions.

The reality is complex, and, regardless of whether language, pair bonding and cooperative breeding are homoplastic or not, using living New World monkeys as models of the origin of human language and sociality may be more productive than trying to piece together fragmentary paleobiological and archaeological evidence from Africa without the luxury of observing language among living apes. An intriguing question can be posed: is human language an extension of tool use, as the evolution from great apes through Oldowan to Acheulian technologies and further suggests, or it’s primarily a means of social recognition? Are words rarefied stone tools or, instead, stone tools are thickened sounds? Is human language the final product of millions of years of tool perfection, or stone tools are just regional adaptations of language-based early human populations? Is the fact that the Upper Paleolithic package, which archaeologists use to define behavioral modernity, is not as clearly visible outside of Europe and Africa indicative of an extensive non-lithic system of adaptation (let’s call it Paleolinguic) that spanned America, Asia and the Sahul from 100,000 to 10,000 YBP and is still manifested in the exceptional richness of kinship systems, language families, grammatical structures, mythological narratives and musical traditions east of the Movius Line? If so, can it ever be pinned down by archaeological methods, or it’s linguistics, folkloristics, social anthropology and ethnomusicology that are the true archaeological sciences? Is technological evolution progressing from more perishable (wood, bone, fiber) to less perishable materials, and hence archaeology is capable of documenting only later stages in technological evolution? Is it possible that the lithic system of adaptation well documented in Europe and Africa is the product of admixture between intelligent but non-lithically minded modern humans and archaic hominins, so that the latter furnished the old-world “hardware” but the former brought with them an entirely new “software”? At the end of the day, modern humans are young, fast, innovative and expansive and they don’t fit the mold of a slowly progressing African primate.

II. Out-of-America, with human origins from an East Eurasian hominid, and into Africa with admixture with extinct African archaic hominins. According to this version of the Out-of-America hypothesis, behaviorally and anatomically modern humans, aka “we,” originated from a population of East Eurasian humans such as Neanderthals (whose geographic reach stretched all the way to the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia and, possibly, beyond the Arctic Circle in the northwestern Urals), Homo erectus or Denisovans (the newly-discovered hominid species attested through a tooth and a pinkie from the Denisova Cave, South Siberia). Between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago, a subset of this original hominid population migrated to the New World (via the Bering Strait Land Bridge), where speciation into modern humans occurred. While, under out-of-America II, the unique social behaviors shared between modern humans and New World primates (pair bonding, paternal investment, cooperative breeding and speech) are interpreted as homoplasies, the fact that such key aspects of human social and cognitive behavior are shared with Platyrrhines suggests that the immediate ancestors of modern humans were exposed to the same New World environment as the New World monkeys.

This migration into a new continent via a relatively narrow land bridge resulted in a population bottleneck still visible in the human genome (as compared to other primate genomes) and in the Amerindian genome. With the next retreat of the ice shield, our ancestors migrated back to the Old World and replaced, possibly with some admixture, all Old World hominids in Eurasia and Africa. As a result of this re-expansion in the Old World, all human populations, with the exception of American Indians (and arguably such isolates as Papua New Guineans, the peoples of the Caucasus and the Hadza of Tanzania), somewhat rebounded from the original bottleneck due to population size growth, waves of intraspecific admixture and, possibly, admixture with archaic hominids in Eurasia and Africa. This replacement of Old World hominids by the modern humans coming out of America corresponds to the emergence of signs of modern human behavior all over the globe around 40,000 years ago. One clear advantage of Out-of-America II over Out-of-Africa is that prolonged geographic isolation is an absolute prerequisite for a speciation event to occur. Africa had been well settled by ancient hominids to allow for the easy and matter-of-fact speciation into modern humans in Africa that’s assumed by the mainstream science of human origins. The emergence of a new hominid species with a radically different, worldwide adaptation based on an advanced system of symbolic thinking and social cooperation followed by the dramatic replacement of pre-existing hominids all over the world is best explained as having its origin in a unique original environment – on a continent previously unexplored by hominids. Another advantage of Out-of-America II over Out-of-Africa is that it’s consistent with ancient DNA results: while we don’t have a single ancient DNA sample to ascertain whether modern African populations are directly related to ancient “anatomically modern humans” (e.g., Omo, Herto, etc.) and hominids in Africa, we do have ancient DNA data (X chromosome, autosomes, blood groups) that document matches between Neanderthal and Denisovan genetic variation, on the one hand, and modern humans in the New World (and in Melanesia). While these matches are currently interpreted as a sign of admixture between Africa-derived modern humans and in-situ hominids, they are the only signs of continuity between archaic and modern humans known to science at this moment.

After speciation in the New World had occurred, early Homo sapiens sapiens colonized first Eurasia and then Africa replacing and admixing with local hominids. Admixture with archaic hominins in Africa was more substantial than in Eurasia, which is reflected in the firmly established excess in intragroup genetic diversity in Africa. This model uses Y-DNA evidence, namely the phylogenetic position of the major African E clade as a subset of the non-African DECF clade, as evidence for the extra-African origin of modern humans. Back in 1998, the Michael Hammer lab published a paper entitled “Out of Africa and Back Again: Nested Cladistic Analysis of Human Y Chromosome Variation,” in which a major back-migration into Africa accounting for the majority of African Y chromosomes was proposed. Haplogroups A and B found exclusively in Africa are explained as either the product of admixture between African hominids and the incoming modern humans or as retentions from the earliest, purely African phase in the modern human evolution. Archaeologically, the presence of sites such as Dabban, with clear Upper Paleolithic roots, in North Africa around 40,000 YBP supports the back-migration idea. From the paleobiological perspective, the Hofmeyr skull in South Africa dated at 36,000 YBP clusters with Upper Paleolithic Eurasians, which, again, suggests that Africa was peopled from Eurasia, not the other way around. Another argument in favor of an extra-African origin of modern humans is the fact that skulls with archaic features survived in various part of Africa (e.g., the Iwo Eleru skull dated at 11-16,000 YBP or the Lukenya Hill calvaria in Kenya at 23-22,000 YBP). If there was indeed continuity between “anatomically modern humans” in Africa that begin to show up in the paleontological record from 200,000 BP on and today’s anatomically and behaviorally modern humans, we would not expect archaic hominins to survive in Africa for almost 180,000 years. Outside of Africa, modern humans needed only a short window to replace all of the Neanderthals. It’s also noteworthy that African megafauna was largely spared in Africa: only 14% (or 7 out of 49 genera) of African megafauna went extinct in the Late Pleistocene. Outside of Africa, megafauna extinctions were much more dramatic, with 86% of megafauna going extinct in Australia, 80% in South America, 73% in North America, 60% in Europe. Under the anthropogenic theory of megafauna extinctions, modern human hunting and ecological disruption are the causes of the extinctions. If Africa was the least affected continent, it’s possible that it was peopled by modern humans later than other continents and/or by smaller numbers of modern humans. But genetics predicts otherwise – Africa must be the oldest and most populous continent, hence modern Africans are more diverse than populations outside of Africa. If anatomically and behaviorally modern humans originated at a place in Sub-Saharan Africa and expanded first across all of Africa (as the distribution of “basal” mtDNA and Y-DNA lineages in current phylogenies seems to suggest), then it’s unclear why the megafauna was not affected by their new and improved hunting practices. But the anthropogenic theory of megafauna extinctions is just one theory out of many and climate change may have been a bigger factor.

III. Out-of-America at the end of the most recent Ice Age. This model presupposes that the New World was peopled by behaviorally and anatomically modern humans significantly earlier than the Clovis archaeological horizon, e.g., 40-20,000 years ago. But then, at the end of the recent Ice Age, New World populations moved back toward Alaska and spilled over into Northeast Asia. This idea was put first forth by the father of American anthropology, Franz Boas. More recently, biological anthropologist Peter Brown hypothesized that such a back-migration from North America to East Asia may have brought the Mongoloid phenotype to the Old World. Brown’s hypothesis rested on an observation that the oldest crania with “Mongoloid morphology” are found in North America; only later do they show up in East Asia. Expanding Brown’s insight beyond craniology, under out-of-America III, a number of genetic and phenotypic traits that are uniquely shared between America and East Asia (high frequencies of the derived variant of EDAR gene or the so-called “Sinodonty” dental pattern) can be attributed to a back-migration from America to Asia some 12,000 years ago. The distribution of Y-DNA haplotypes fits well with out-of-America III. Typical East Asians hgs N and O (as well as hgs C1-C2-C4-C5 found in East Asia and the Sahul recently grouped into one clade by phylogenists) are not found in the Americas, while hg C3 (found in North America as C3b and in South America as C3*) is shared between America and East Asia. This suggests that C3 must have migrated from America to Asia, and not the other way around. If the migration went from Asia to America, we would expect to find hgs N and O in America but this is clearly not the case. The necessary conclusion drawn from different datasets is that the special affinity between Amerindians and East Asians stems not from a recent migration from East Asia to America, but from a migration that went the other way, from America to Asia. Prior to 12,000 years, therefore, America and East Asia were likely quite distinct biologically, or at least not much closer than America and the Sahul, or America and West Eurasia.

A Holocene back-migration from the New World to the Old World is consistent with both Out-of-America I (see Hicks, Alvah M. 1998. Alternative Explanations for Similarities between Native Americans and Siberians // Human Biology 70 (1): 137-139) and Out-of-America II. Out-of-America III is very defensible archaeologically, as Clovis seems to have originated from the Buttermilk Complex in Texas (15,500 YBP) and fluted projectile points appear in Alaska (Mesa, Serpentine Hot Springs) and Northeast Asia (Uptar) at much later dates. A number of mtDNA (A2a, C1a), Y-DNA (Q1a3a1) and microsatellite (9-repeat allele at microsatellite D9S1120) lineages also seem to have leaked to Siberia from the New World (see Tamm et al. “Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders”; Kemp & Schurr, “Ancient and Modern Genetic Variation in the Americas”), which means archaeology, paleobiology and genetics are in good alignment on this issue. But nobody has so far formalized these recent findings into a theory. Academic scholars’ hesitation may stem from the fact that if a back migration happened at a time when America was presumably colonized, then science is short of data illustrating how and when the colonization of the New World happened in the first place.

IV. Out-of-America, with human origins from an East Eurasian hominid and with a “back-migration” at the end of the most recent Ice Age. The marriage of Out-of-America II with out-of-America III results in a model whereby there were two migrations out of America – in the Late Pleistocene and in the Early Holocene. The Early Holocene migration out of North America into North(east) Asia may have also affected Central and South America, which can account for some of the genetic homogenization observed in American Indians and for some pan-American phenotypical traits such as broad skulls and shovel-shaped incisors. The traits that are usually considered as evidence of an Asian origin of American Indians are hereby re-interpreted as evolving in northern North America or in the Beringian refugium at the end of the Ice Age and re-expanding, with the retreat of the glaciers, all the down way into island Southeast Asia on the Old World side and South America on the New World side. The signal of American Indian genetic homogeneity often reported by genetic labs may be the result of gene flow from North to South America replacing more divergent and ancient lineages.

All three models are at odds with the mainstream theory of the “peopling of the Americas.” Even the mildest version of Out-of-America, namely Out-of-America III, is a scientific revolution. As Hamilton & Buchanan write, “for humans to have colonized the Americas much before Clovis…would require major changes to the northeast Eurasian Upper Paleolithic archaeological record, including a much faster colonization velocity, no expansion hiatus, and a Beringian archaeological record more than twice as old as current evidence suggests.” However, the mainstream science of human origins operates with a limited number of interdisciplinary resources, is methodologically incoherent and is biased toward archaeological and genetic interpretations. Archaeology and genetics are treated as if they were grounded in divine revelation, as every find and pattern is interpreted as automatically deciding the issue of who came from where. Back in the early 1900s, when Ales Hrdlicka was enforcing his will to see America peopled “no earlier than 5,000 years ago,” linguists such as Edward Sapir were “herding cats” trying to subsume the phenomenal diversity of American Indian languages into a reasonable number of stocks. By the end of the 20th century, it has become apparent that the New World harbors 2/3 of world language diversity and can hardly have been peopled 5,000 or even 15,000 years ago. The deep disjunction between archaeology and linguistics has made the final solution (Endlösung) for “the peopling of the Americas” either in the form of Hrdlicka’s model or the later Clovis-I model a myth told in the language of scientific facts and a genocide of scientific objectivity. With the recent demise of both the Out-of-Africa with Complete Replacement model of Old World human origins (from 2010 on) and the Clovis-I model of New World human origins (from the late 1990s on), interdisciplinary data has finally converged on Out-of-America III and IV as two viable alternatives to mainstream academic and popular science, the alternatives that are more objective, more grounded in multi-field anthropological knowledge, more innovative and have more explanatory power.

Out-of-America III and IV provide very parsimonious alternatives to the mainstream science of human origins: they operate with the traditional geographic route connecting the Old World and the New World, namely the Bering Strait Land Bridge. They don’t digress into any “fringe” theories of human dispersals such as the destructive impact of the Toba eruption on South and Southeast Asian human populations, the catastrophic impact of a supernova explosion on North America or the formative role of prehistoric trans-Atlantic (think of Stanford and Bradley’s Solutrean hypothesis) and trans-Pacific (think of Tor Heyerdahl) voyages; neither do they resort to such artificial, Atlantis-like explanatory devices as the idea of a sunken “Beringian refugium” leading to “Beringian Incubation” (e.g., Kemp & Schurr, “Ancient and Modern Genetic Variation in the Americas” In Human Variation in the Americas, 2010, p. 27), the “Arabian refugium” idea or the pre-desertification Sahara homeland idea used by some academic scholars and amateurs to explain the genetic and phenotypical specificity of American Indian populations vs. Asians or non-African populations vs. Africans. Out-of-America III and IV simply revert the directionality of human migrations at key geographic junctions to generate testable alternatives.

As we begin repositioning America from the ultimate destination of human dispersals in the Late Pleistocene-early Holocene to their source, it immediately challenges the central role of Africa in human prehistory. It’s therefore important to revisit the existing versions of the out-of-Africa theory.

I. Out-of-Africa with Complete Replacement. This theory, which dominated the science of human origins from the early 1990s to 2010, posits that modern humans expanded out of Africa 50-40,000 years ago and completely replaced, without admixture, Eurasian hominids (Neanderthals and Homo erectus).

II. Out of Africa with Complete Replacement and with a Back Migration. The only difference between Out-of-Africa I and Out-of-Africa II is that Out-of-Africa II admits small migrations back to Africa after 40,000 YBP. This model is based on the presence of derived M (M1) and N (U6, N1a) mtDNA lineages in Africa.

III. Out-of-Africa with Archaic Admixture and a Back Migration. This model based on the studies of ancient DNA obtained from archaic hominids is currently supported by the majority of academic scholars. As behaviorally and anatomically modern humans fanned out from Africa, they experienced gene flow from the in-situ archaic hominids such as Neanderthals and Denisovans. Sometime after 40,000 YBP there was a small back migration of modern humans back into Africa, as supported, again, by a few minor M and N mtDNA lineages. Out-of-Africa III is a mirror image of Out-of-America III (see above): both allow minimal back migrations, from Asia to Africa and from America to Asia, in relatively recent times.

IV. Out-of-Arabia/India with Archaic Admixture in Eurasia and Africa. This model shifts the origin of anatomically and behaviorally modern humans away from Africa to Arabia or even further to India. Africa remains the source for a population that has been undergoing modernization since 200,000 years ago. But to fully evolve into anatomically and behaviorally modern humans our ancestors needed an extra-African geographic locus to actually shed off the last archaic morphological and behavioral features and speciate into “us.” This model dates the founding out-of-Africa migration of proto-Homo sapiens sapiens to 120,000-100,000 YBP, which is roughly 50,000 years or two times earlier than the dates provided by the out-of-Africa with Complete Replacement model (Model 1 above). What happened at roughly 40,000 YBP is a back-migration into Africa. So, after speciation had occurred, early Homo sapiens sapiens colonized not only Eurasia but also Africa replacing and admixing with local hominids. This model uses Y-DNA evidence, namely the phylogenetic position of the major African E clade as a subset of the non-African DECF clade, as evidence for the extra-African origin of modern humans. Back in 1998, the Michael Hammer lab published a paper entitled “Out of Africa and Back Again: Nested Cladistic Analysis of Human Y Chromosome Variation,” in which a major back-migration into Africa accounting for the majority of African Y chromosomes was proposed. Haplogroups A and B found exclusively in Africa are explained as either the product of admixture between African hominids and the incoming modern humans or as retentions from the earliest, purely African phase in the modern human evolution. Archaeologically, the presence of sites such as Dabban, with clear Upper Paleolithic roots, in North Africa around 40,000 YBP supports the back-migration idea. From the paleobiological perspective, the Hofmeyr skull in South Africa dated at 36,000 YBP clusters with Upper Paleolithic Eurasians, which, again, suggests that Africa was peopled from Eurasia, not the other way around. Another argument in favor of an extra-African origin of modern humans is the fact that skulls with archaic features survived in various part of Africa (e.g., the Iwo Eleru skull dated at 11-16,000 YBP) almost into the Holocene. If there was indeed continuity between “anatomically modern humans” in Africa that begin to show up in the paleontological record from 200,000 BP on and today’s anatomically and behaviorally modern humans, we would not expect archaic hominins to survive in Africa for almost 180,000 years. Outside of Africa, modern humans needed only a short window to replace all of the Neanderthals. It’s also noteworthy that African megafauna was largely spared in Africa: only 14% (or 7 out of 49 genera) of African megafauna went extinct in the Late Pleistocene. Outside of Africa, megafauna extinctions were much more dramatic, with 86% of megafauna going extinct in Australia, 80% in South America, 73% in North America, 60% in Europe. Under the anthropogenic theory of megafauna extinctions, modern human hunting and ecological disruption are the causes of the extinctions. If Africa was the least affected continent, it’s possible that it was peopled by modern humans later than other continents and/or by smaller numbers of modern humans. But genetics predicts otherwise – Africa must be the oldest and most populous continent, hence modern Africans are more diverse than populations outside of Africa. If anatomically and behaviorally modern humans originated at a place in Sub-Saharan Africa and expanded first across all of Africa (as the distribution of “basal” mtDNA and Y-DNA lineages in current phylogenies seems to suggest), then it’s unclear why the megafauna was not affected by their new and improved hunting practices. But the anthropogenic theory of megafauna extinctions is just one theory out of many and climate change may have been a bigger factor.

The Out-of-Arabia/India model advanced by Dienekes (e.g. here, here, here and here, see especially the Comments section; also here in the Comments section) provides an elegant counterpart to Out-of-America IV. Out-of-Arabia/India explains the excessive diversity in Africa observed across multiple genetic systems not as a result of greater antiquity of modern humans in Africa than elsewhere but as a result of admixture between archaic hominids in Africa and modern humans who arrived from Asia. In a manner of continuing this logic, the low diversity of American Indian populations are consistent with the absence of archaic hominids in the New World. Genetic diversity levels have, therefore, nothing to do with a populations antiquity but with the degree of admixture with archaic humans. New World populations represent the “purest” type of modern humans that have never admixed with archaic hominids in the Old World (but are ultimately derived from an archaic hominid population in East Eurasia). As unadmixed modern humans, they naturally become the source of modern humans in the Old World. Dienekes rejects America as a possible homeland for modern humans, but his logic is circular and is driven by inertia, rather than by actual data. For instance, he writes, “The evidence is slowly mounting for the place of origin of fully modern H. sapiens, as region after region strikes out by having archaic humans present when they are not supposed to be there. Both Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia have struck out, and Europe had already struck out because of its documented Neandertal population. Australasia is not a valid option due to the lack of precursors, and the Americas because of the their late settlement.” Needless to say, one shouldn’t be rejecting out-of-America on the premise that America was settled late. As I noticed, my comments on Dienekes’s site over the past two years helped Dienekes shape his Out-of-Arabia/India model (as well as his out-of-the-Caucasus theory for the peopling of Europe) to mimic some properties of the out-of-America thinking. Lower intragroup genetic diversity and high linguistic diversity are plausible indicators of antiquity of modern human populations in a given region. What gives Out-of-America IV an edge over Out-of-Arabia/India is America’s unparalleled linguistic diversity suggestive of the great antiquity of a defining characteristic of behavioral modernity there. India and especially Arabia have nothing to offer in terms of linguistic diversity.

[…] a process of phonemic diversity loss between Africa and the rest of the world. However, under the out-of-America II model it’s precisely the New World and Australasia that enjoy the greatest antiquity of modern […]

How about this one? One branch of Australopithecus becomes Gigantopithecus/Bigfoot in East Eurasia, enters America, and then becomes smaller again in size (perhaps in the Tropics) to become Homo Erectus (which IS by now the species Homo Sapiens, but a more primitive-looking subspecies), migrates back to Asia, and returns to Africa via the Acheulo-Yabrudian industries in Israel. Yet, one lineage stayed in America, resulting in the Middle Paleolithic “pre-lithic horizon”, and mixes with Upper Paleolithic lineages coming back to America from Asia (Dyuktai/Cordilleran) and Europe (Solutrean).

So, for support of out-of-America III, would we not need to document the presence of Denisovan admixture moving into Africa in a gradient with decreasing frequencies from North to South (baring Khoisan migrations)?

This evidence is missing from the puzzle so far.

Hi Gerry,

I would need to know more why you think so. Out-of-America III is basically a back migration out of America at the end of the Ice Age, which was either limited in scope (the Boasian back migration accounting for the Paleoasiatic peoples and Kets) or extensive accounting for the sudden spread of a new Mongoloid phenotype in Asia. OOAm III has no bearing on any migrations into Africa, although it mirrors nicely with either a limited or extensive migration(s) out of Eurasia into Africa in the past 40,000 years postulated on the basis of autosomal, mtDNA and Y-DNA.

Please elaborate on your question.

Mr. Dziebel,

I have worried for the past year that my above hasty comment (which still shows up prominently when I google myself) appears to be derisive or even a slur, for which I apologize. At the time I thought I was cobbling together a scheme to accomodate OOAmerica I and II in one swoop…without even having carefully read either I or II.

Since then I have realized that OOAmer. I is in the vast realm beyond the scope of my anthropo-hobbying.

Yet, the idea of OOA II has grown on me with time and piqued my sense of wonder. I would put the migration earlier than 40k BP, though, so as to be in time for Maju’s (forwhattheywereweare blog) 47k BP start of Upper Paleolithic in Baikal region.

Here’s the thing…based on genetic haplotypes, I didn’t see how OOAmer. II could be possible without any presence of mtDNA L lineages in America…until the day I saw a map of mtDNA pie charts that showed ample L throughout the eastern parts of South America!

I would be interested in reading further on analyses you’ve done regarding these L groups.

Also, I agree in the high probability of at least some degree of OOAmer. III.

(for instance mtDNA C1 turning up somewhere near Finland in epi-paleolithic, I believe….and D4h3 in Shandong, China, etc. I wonder if D4h3 represents a coastal culture stretching from Fraser R. to Amur R. until wiped out by a tsunami and largely replaced by mtDNA A in Alaska, etc.)

Hi John,

The out-of-america vs. out-of-Africa piece on this site is a blurb which I’ll keep updating as thinking evolves.

I’m totally fine with the dates earlier than 40K. In fact the recent molecular dates for the back migration of wooly mammoths into the Old World (sic!) are on the order of 60K.

Regarding mtDNA L lineages. I have serious issues with mtDNA dating and mtDNA phylogeny. I went into some degree of detail on the latter at Anthrogenica most recently. In a word, the mtDNA phylogeny contradicts ancient DNA data from Denisova and Sima and I think it needs to be synched with it before we proceed any further. It was built in pre-ancient DNA times and hasn’t been updated since. But even if L lineages have been properly defined, I currently interpret (some of) them as admixture from African archaic hominins. They are not found outside of Africa and considering that Africa is very homogenous linguistically compared to America and PNG and language is a hallmark of behavioral modernity, it’s possible L lineages got into the human mtDNA pool from archaic hominins who subsequently went extinct.

To your point, though, just like it’s possible that Y-DNA R is one of indigenous Amerindian lineages of North America, South America may harbor geniune L lineages. In both cases, post-1492 migrations from Europe and Africa confused the picture.

Interesting article. The peopling of the world is indeed complex. We will eventually figure it out – we need more fossils and dna.

My thoughts about immigration to the new world.

http://dnaamerica.blogspot.com/

I am not sure about human originating in the Americas, but what I find extremely interesting is that some South American monkeys have faces very alike to humans.

They also have a pair of 23 chromosomes like humans. I am referring to the

The Red uakari (Cacajao calvus) and Coppery titi monkey (Callicebus cupreus) of South America have 46 chromosomes like humans.

The uakari (Cacajao calvus, is very interesting because male lose their head hair like humans; and their face is very human like.

Some pictures of uakaris http://www.canstockphoto.com/images-photos/uakari.html