The Stereotype of a Beringian Refugium

The new paper “Mitochondrial DNA Signals of Late Glacial Recolonization of Europe from Near Eastern Refugia” by Maria Pala et al. (2012) seemingly has nothing to do with the “peopling of the Americas.” It argues, on the basis of a modern European mtDNA sample that mtDNA J and T subclades entered Europe prior to the Neolithic, with the post-LGM population re-expansion from a Near Eastern refugium. But in the opening of the paper they write the following:

“The last Ice Age, which ended 11.5 thousand years (ka) ago, was an era of great climatic uncertainty, with dispersed populations in some regions driven into safe havens at times of greatest stress such as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), ~26–19 ka ago. Investigating these glacial refugia has long been a favorite pursuit of phylogeographers. The genetic diversities of many species across a huge taxonomic range have been mapped to various putative refugia, often but not always at low latitudes. Perhaps the clearest example is the Beringian refugium, from which modern humans spread into the Americas.”

For the idea of a Beringian refugium, they cite Perego et al. (2009), Perego et al. (2010) and Tamm et al. (2007). The Beringian refugium is a legitimate hypothesis trying to explain the origin of American Indian linguistic and genetic variation. But Pala et al (2012) make it look like it’s an established fact that can be exported “as is,” without qualification, into a study of West Eurasian glacial refugia. It’s of course possible that some human populations were stuck in Beringia and then expanded out of it as the ice melted and Beringia submerged. But Pala et al. use Beringian refugium to refer to a geographic area that supposedly explains the origin of all of the American Indian populations. If only a few populations inhabited a Beringian refugium during the most recent Ice Age it would be much harder to detect their post-glacial spread than if the progenitors of all of New World populations were locked there.

What one would expect to find in the modern human linguistic and genetic variation as well as in archaeological data that might suggest that a glacial refugium existed and it left an indelible mark on modern populations?

Linguistically, one might expect to see an excess in diversity, as measured by language stocks or typological features, in the areas adjacent to the refugium. In the case of Beringia this is not the case: northern North America and Northeast Asia are not richer in language families or typological features than southern North America, Mesoamerica and South America. The only linguistic classification that suggests higher stock diversity in northern North America and Northeast Asia is Greenberg’s tripartite classification of American Indian languages into Eskimo-Aleut, Na-Dene and Amerind. Members of all three families are found in the geographic areas adjacent to Alaska, while Mesoamerica and South America have languages belonging to the Amerind phylum only. However, Greenberg’s classification is rejected by all specialists in American Indian languages and is currently off the table.

Genetically, again, one might expect to find an excess in genetic diversity in the areas adjacent to a refugium. In the case of Beringia, this is again not the case. For example, mtDNA hgs X and B are rare to non-existent in northern North America and Northeast Asia, while they are wide-spread further down south and are frequently found in combination with hgs A, C and D. Northern Amerindian populations tend to have a limited number of mtDNA lineages at high frequencies. Northern Athabascans are mostly hg A, Eskimo-Aleuts are hgs A and D. This suggests that the modern New World populations living in the areas adjacent to Beringia colonized these territories from elsewhere in the Americas.

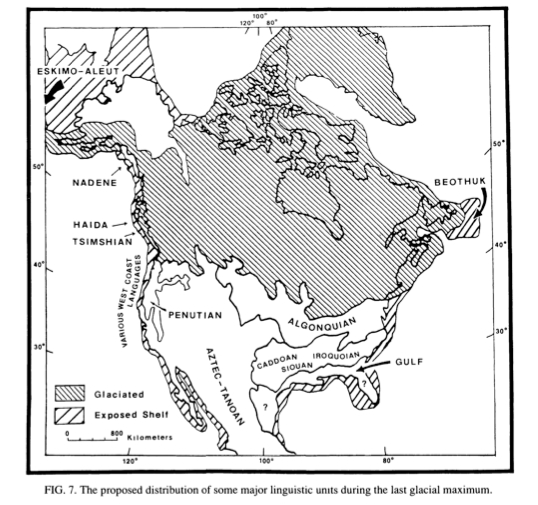

Archaeologically, one should expect to find in the geographic area that served as a refugium during the last Ice Age technological prototypes of toolkits observed in the younger strata of the areas colonized from this refugium. As of now, there’s simply no archaeological evidence for a Beringian standstill happening before the founding migration down the coast or an ice-free corridor into the southern areas of the New World. This evidence may be submerged under water but it’s definitely not there now. Instead, what archaeology has been telling us in the past 15 years is that human populations were present in the New World south of the ice shield (e.g., Monte Verde in Chile), that Clovis originated in southern North America (Buttermilk complex in Texas) and that Clovis-type points moved north into Alaska and Northeast Asia (Mesa, Serpentine Hot Springs, Uptar). Instead of thinking of Beringia as a refugium for the New World, we need to start thinking about the New World as a Pleistocene refugium for the post-glacial Circumpolar spread zone. In a number of publications Richard A. Rogers et al. provided precisely such a model: they showed a surprisingly good fit between the distribution of modern language families and the Pleistocene ecological zones (see below, Fig. 7 from Rogers et al. “Ice-Age Geography and the Distribution of Native North American Languages,” Journal of Biogeography (1990) 17, 131-143) and concluded on the basis of this isomorphism that humans must have been present south of the ice shield in America.

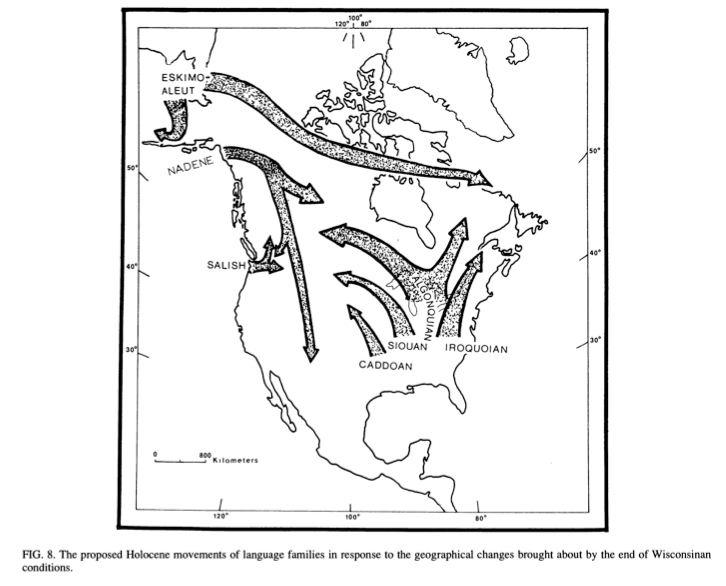

They argued for this at a time when archaeology did not have fully legitimate pre-Clovis sites and they were right. Note that they assigned only Eskimo-Aleuts to a Beringian refugium (or the Saiga Faunal Province), with Na-Dene speakers, Haida and Tsimshian occupying a coastal one and the rest of American Indian language families maintaining their distribution south of the glaciated areas of North America, with Algonquians inhabiting the Symbos-Cervalces Faunal Province, the Uto-Aztecans and Tanoans the Camelopes Faunal Province, the Gulf languages the Chlamyrhere-Clyprodont Faunal Province, the Siouan, Caddoan and Iroquoian languages the Odocoileus-Pitymys Faunal Province, etc. They arrived at the following model of population expansion after the break-up of the ice shield:

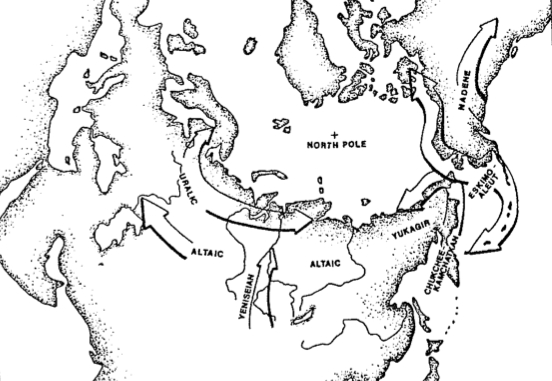

It makes good sense and offers an unacknowledged compromise between the various models of the peopling of the Americas and linguistic classifications. Eskimo-Aleuts and Na-Dene re-expanded into their present territories from glacial refugias, one of which was in Beringia. Salishan, Caddoan, Siouan, Algonquian and Iroquoian languages pushed up north diffusing Clovis-type lithic technologies into Na-Dene, Eskimo-Aleut ranges and further out into Northeast Asia (Uptar site at 8,600 YBP). In an earlier paper (“Language, Human Subspeciation, and Ice Age Barriers in Northern Siberia,” Canadian Journal of Anthropology 5 (1), 1986, pp. 11-22), Richard Rogers applied the same logic to Northeast Asian language families (Chukchee-Kamchatkan, Uralic, Altaic and Yeniseian) and arrived at the following map.

It makes good sense and offers an unacknowledged compromise between the various models of the peopling of the Americas and linguistic classifications. Eskimo-Aleuts and Na-Dene re-expanded into their present territories from glacial refugias, one of which was in Beringia. Salishan, Caddoan, Siouan, Algonquian and Iroquoian languages pushed up north diffusing Clovis-type lithic technologies into Na-Dene, Eskimo-Aleut ranges and further out into Northeast Asia (Uptar site at 8,600 YBP). In an earlier paper (“Language, Human Subspeciation, and Ice Age Barriers in Northern Siberia,” Canadian Journal of Anthropology 5 (1), 1986, pp. 11-22), Richard Rogers applied the same logic to Northeast Asian language families (Chukchee-Kamchatkan, Uralic, Altaic and Yeniseian) and arrived at the following map.

Historically and arguably presently, American Indians have been subject to a host of popular stereotypes. (See, e.g., “The White Man’s Indian,” by Robert Berkhofer.) Scientists are not immune to these stereotypes. Pala et al. (2012) uncritically interpreted some publications advocating for a Beringian refugium as a jumping board for the peopling of the Americas in order to provide a firm foothold for their interpretation of the peopling of Europe. The assumption is that Beringian refugium is a fact. But the truth is that the Beringian refugium is a conceptual device used to make the old Clovis I model work in the face of a growing body of cross-disciplinary evidence against it. It also serves the purpose of finding a strategic balance between a single origin model and a multiple-migration model for the peopling of the Americas: one migration brought the founding population to the Beringian refugium from which subpopulations began to be dispatched into the new continent as deglaciation allowed. But these are conceptual compromises that will change once the contradicting data reaches a tipping point to overturn the paradigm. They are unrealiable as models to be exported as proven case studies to the Old World regions. One may also recall the early studies of worldwide genetic variation by Luca L. Cavalli-Sforza who assumed that the recent peopling of the Americas was a fact set in stone by archaeology. He then noticed that genetically American Indians are the exact opposites of Africans and concluded that Africans must be the oldest, since American Indians are the youngest. The truth is archaeology doesn’t have the facts to prove the 12-15,000 year old colonization of the New World. It’s an intellectual model at best and a stereotype at worst that cannot be reliably used to kickstart the far-reaching interpretations of human genetic history from the genetic perspective.

At the same time, innovative interdisciplinary approaches such as Richard Rogers’s need to be experimented with beyond the North American and Northeast Asian language families, and Western Eurasia analyzed genetically by Pala et al. (2012) is a very suitable region for the study of isomorphisms between the distribution of language families and ancient biogeographies.

It seems your point here has now been confirmed by Sandoval et al., Y-chromosome diversity in Native Mexicans reveals continental transition of genetic structure in the Americas

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.22062/abstract

‘Mexico might have constituted an area of transition in the diversification of paternal lineages during the colonization of the Americas.’

I guess Amerindian Q3-M3 developed far south from Beringia in the neighborhood of Mexico, and from there it migrated south, and also ‘back north’, only more recently- ie. at least already 10 kya.

Hi Rokus,

Sorry, I’ve been out of the country and haven’t had a chance to respond. Under out-of-America III Q-M3 indeed originated in middle America from Q-M242 as a result of the founding migration of Homo sapiens to the New World at roughly 40,000 YBP and migrated back to Northeast Asia roughly 10,000 YBP. In view of the multiple uncertainties with the molecular clock, I don’t see any compelling reasons to believe that Q-M3 is 15,000 years old.

Under out-of-America II, Q-M3 is the most divergent Q lineage, with the T allele inherited from a Eurasian hominin, retained only in the New World and among Paleosiberian populations and with other Q carriers shifting back to C (homoplastic with chimps). In the latter case, the tree would look more like the X chromosome tree (see http://anthropogenesis.kinshipstudies.org/2012/03/american-indians-neanderthals-and-denisovans-pca-views/), where the most divergent B006 lineage attested in Neandertals is found at high frequencies in the Americas followed by West Eurasia. I can also see similarities in the distribution of Y-DNA hg Q and the distribution of the “Amerindian component” detected in autosomal studies (see http://anthropogenesis.kinshipstudies.org/2012/03/admixture-an-amerindian-component-in-eurasian-populations-3/).

I agree Q-M3 could be older, but I am very wary of any type of predicated or proposed SNP homoplasticity. I even consider it most unlikely that the R1a1-defining SRY10831.2 mutation, that ‘reverses’ the SRY10831.1 mutation of BT haplogroups on two basepairs (C->T, G->A) out of a string of 691 basepairs, could have happened independently from the ancestral form in YDNA haplogroup A – and more so since both R1a1 and A equal the full string observed in chimps. Or maybe we are still missing some genetic principles here?

The good news for you here might be that without the need for homoplasticity a ‘reversed’ tree becomes a possibility, with the earliest fork at A and R1a1 – thus Q forking just a little later and well before ‘the rest’.

Anyway, genetic and cultural contribution from the Americas may be an attractive alternative. I am just thinking of the American custom of cranial deformation, leading to occipital flattening and hyperbrachycephaly – a fashion that may have started there and may have been accompanied by an important world-wide selective force into the direction of fairly recent brachycephalic tendencies.

Nice builds, Rokus, thanks. I wonder if you’ve seen Klyosov/Rozhanskii’s new paper (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa/) in which he argues for the same connection between hg A and R1a1, both stemming from an ancestral “alpha-haplogroup” of not necessarily African origin.

As for Y-DNA hg R1, Amerindians often show it at high frequencies but it’s usually assumed that it’s the product of recent admixture with Europeans. In light of what you wrote, this may not be the case everywhere, so that some of R1s in Amerindians came indeed by way of admixture, while others have great antiquity.

I’ve never thought about head deformations in the same way and haven’t tracked the distribution of this custom globally, but it’s an interesting idea. What I did notice is that South American shamanism shows forms that are neutral with respect to the expressions of the two polar types of shamanism in the Old World – the systems that are build around the idea of a traveling soul of a shaman and the systems that are centered on the idea of a shaman being possessed by a spirit. This means symbolic culture may, too, carry the out-of-America “footprint” and we may find similar dynamics in the area of head deformations.