Reader Questions 1: In Search of Archaic Hominin Survivals in Eurasia. Tutkaul Culture

This is a new category of posts on this weblog. Every now and then a reader sends me a question and sometimes I get interested and try to answer. There seems to be a steady interest on the part of Western readers to know more about research conducted in Russia and the former Soviet Union (which is 1/6 of the globe) by Russian and Soviet scholars and published exclusive in Russian. My introduction into the work of Yuri Berezkin on the areal distribution of mythological motifs in the New World and beyond (here and here) is one case in point. A reference to my book “The Genius of Kinship” (2007) recently made by the British social anthropologist Nick Allen in the context of the unusual Siberian kinship systems completely unknown in West is a related occurrence.

Since the rise of the “archaic admixture” theme in modern human origins research (beginning with the announcement of the minimal 1-4% admixture with Neandertals in modern non-Africans in 2010), both professionals and amateurs have rushed to search for archaic retentions in relatively recent craniological materials and lithic technological complexes. The Iwo Eleru skull in West Africa dated at 11.7-16.3 KYA showed affinities with archaic African hominins (Harvati K. et al. 2011. “The Later Stone Age Calvaria from Iwo Eleru, Nigeria: Morphology and Chronology,” PLoS ONE 6(9)). Then, Holocene Longlin and Maludong remains in South China were presented (Curnoe D., et al. 2012. “Human Remains from the Pleistocene-Holocene Transition of Southwest China Suggest a Complex Evolutionary History for East Asians,” PLoS ONE 7(3); see my commentary based on known “archaic retentions” in historical Amerindian populations) as having archaic features.

Recently, blogger faintsmile1992 started a discussion at Anthroscape apropos the three papers by Anne Dambricourt Malassé and colleagues regarding Mesolithic and Neolithic skulls and lithics available from the poorly known and poorly accessible Himalayan and Hindu-Kush areas in South-Central Asia. Dambricourt Malassé & Gaillard (“Relations between Climatic Changes and Prehistoric Human Migrations during Holocene between Gissar Range, Pamir, Hindu Kush and Kashmir: The Archaeological and Ecological Data,” Quaternary International 229 (1-2), 2011) write:

“Only four Mesolithic skeletons are known from the excavated site of Tutkaul: two women and two children. The skulls alone have been described. The adults had developed robust features and they cannot be related to any geographical type (Kiyatkna and Ranov, 1971; Dambricourt Malassé, 2008).”

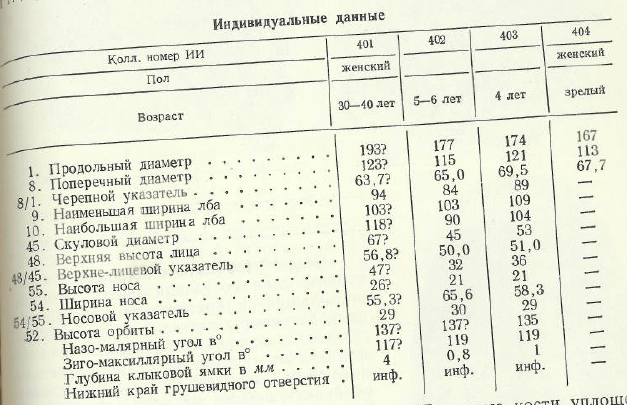

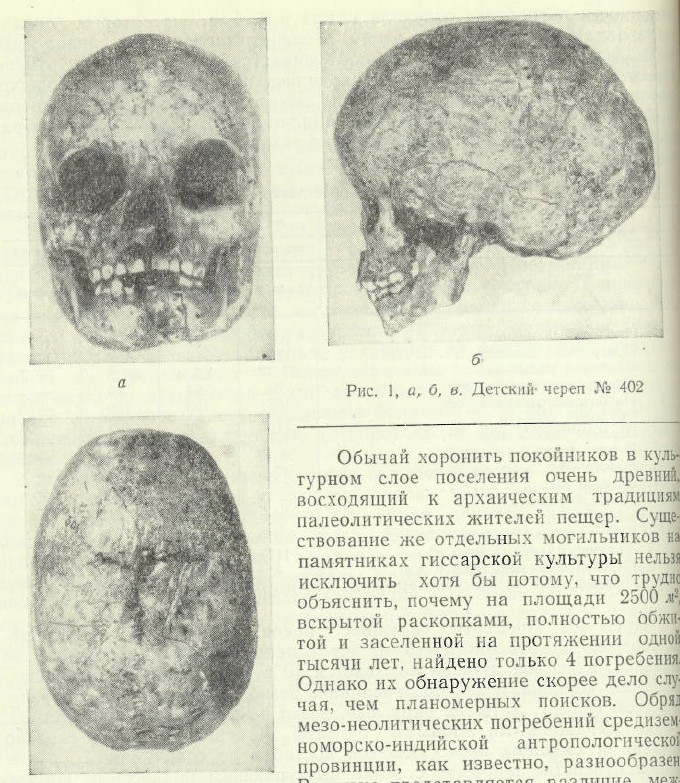

Faintsmile1992 contacted me with a query as to the content of Kiyatkina T.P. & V.A. Ranov. 1971. Perviy antropologickie naxodki kamennogo veka Tadjikistana (neoliticeckie cherepa yz Tutkaula),” Voprosy antroplologii 37, 149–156), a Russian-language publication from a journal now relegated to a remote storage in college libraries. Although not fully incorrect, the description of Tutkaul skulls by Dambricourt Malassé & Gaillard is oversimplified and imprecise. Indeed, 4 skulls were unearthed from the Neolithic levels at Tutkaul (Tajikistan), all buried in a fetal position and all posthumously deformed by a side squeeze. The sex attribution of the 2 adult skulls proved to be difficult. Only one of them showed higher robusticity, which suggests that it may have been the skull of a male. But other traits contradict this conclusion. The Soviet physical anthropologist Tatiana Kiyatkina classified the dolichocranic skulls (see below, only children’s skulls were depicted in Kiyatkina & Ranov 1971) as belonging to the Mediterranean subtype (slight alveolar prognatism) of the general Caucasoid type and noted some of their undifferentiated Caucasoid traits. She measured the skulls using a standard table but many metrics (see below) did not make the final table or have question marks against them because the skulls are artificially deformed.

The skulls also reminded her of Giuseppe Sergi‘s “Euroafrican” race from which the Mediterranean type presumably evolved. Browridges – not visible in the children’s skulls below – do give the skull of the robust adult an archaic feel but they are nowhere near the supraorbital toruses seen in Neandertal skulls and, again, may be sex-based. Dambricourt Malassé & Gaillard’s sentence above created an unwarranted mystique about the Tutkaul skulls for which the original source gives little reason.

The skulls also reminded her of Giuseppe Sergi‘s “Euroafrican” race from which the Mediterranean type presumably evolved. Browridges – not visible in the children’s skulls below – do give the skull of the robust adult an archaic feel but they are nowhere near the supraorbital toruses seen in Neandertal skulls and, again, may be sex-based. Dambricourt Malassé & Gaillard’s sentence above created an unwarranted mystique about the Tutkaul skulls for which the original source gives little reason.

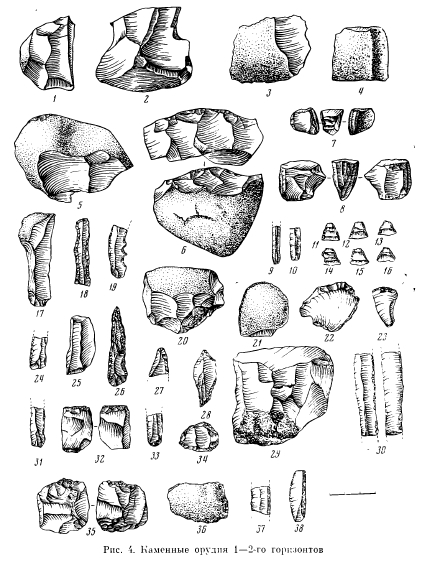

This said, archaeologically Mesolithic and Neolithic Tutkaul is peculiar due to  the central role played in the toolkits by cobblestone based choppers and choppings (see left , from

the central role played in the toolkits by cobblestone based choppers and choppings (see left , from  Ranov V.A., G.F. Korobkova. 1971. “Tutkaul – mnogoslojnoe poselenie gissarskoj kul’tury v Yuzhnom Tadjikistane,” Sovetskaia arckheologiia 2, 133-147). Tutkaul people did hunt (the remains of a deer were found there) but they completely lacked projectile points. Ranov & Korobkova (1971, 142) hypothesized that subsistence was basically pastoralism, with hunting and gathering playing a subsidiary role, hence only pebble-slinging bows were used. Incidentally, pebble-slinging bows, or gulaks, survived in contemporary ethnographic cultures of Central Asia (see a Zhang Xian picture on the right), but they were only used to shoot small birds and animals.

Ranov V.A., G.F. Korobkova. 1971. “Tutkaul – mnogoslojnoe poselenie gissarskoj kul’tury v Yuzhnom Tadjikistane,” Sovetskaia arckheologiia 2, 133-147). Tutkaul people did hunt (the remains of a deer were found there) but they completely lacked projectile points. Ranov & Korobkova (1971, 142) hypothesized that subsistence was basically pastoralism, with hunting and gathering playing a subsidiary role, hence only pebble-slinging bows were used. Incidentally, pebble-slinging bows, or gulaks, survived in contemporary ethnographic cultures of Central Asia (see a Zhang Xian picture on the right), but they were only used to shoot small birds and animals.

Ranov classifed Tutkaul as a Gissar culture. He found similar “primitive” lithic toolkits at Osh-Khona, near the Kara Kul Lake, and at Karatumshuk and coined the term “Gissar enigma.” The origin of these primitive hunters is unclear but judging by the Tutkaul skulls they had neither “Oriental,” nor “Neandertal” affinities. Modern humans are characterized by diverse adaptations and the notion of a “behaviorally modern package” borne out of earlier Cro-Magnon blade-based toolkits is too limiting to capture this adaptational complexity. An argument against the concept of a “behaviorally modern package” was made by a number of archaeologists who reference Australia and Southeast Asia as regions in which this package is not fully visible well into the Holocene. Mesolithic and Neolithic Tutkaul culture in Central Asia shows that even populations with clear West Eurasian affinities lacked “behaviorally modern package” in the Holocene times. They likely practiced pastoralism but the lithic tools were no more advanced than Lower Paleolithic Soanian culture from the same general region. On the other hand, it’s becoming increasingly clear that many of those “behaviorally modern” traits (use of ochre, ornamentation, blade production, etc.) were found in Neandertals further illustrating the objective difficulties of defining behavioral modernity by means of archaeological arifacts.

Thank you.

Judging from the way their phenotype seems mismatched with their tool industry it might seem appropriate to suggest the Gissar people were former food producers driven to a marginal and economically dependent status as was the case with certain hunter gatherers elsewhere in the world. But that wouldn’t explain what they lacked (ie. bows).

Following what happened in Africa – the phenotype of LPA people becoming modified by that of the blacks due to extensive admixture – it might still be interesting to know what the autosomal DNA of the Gissar-Markansou toolmakers was like.

I had expected Dambricourt-Malasse to be hinting that the reason the Tutkaul skulls are unassignable to a ‘geographical type’ (her words) is because they possess some unusual archaic trait like the angular torus she found in Neolithic South Asians. Or at the very least that the Tutkaul people retained a plesiomorphic phenotype unspecialised in the direction of the familiar major races, and this made them parallel to the survivors such as Ainu, Andamanese, Veddahs etc.

That the culture of these people is continuous from the Soanian is attested by what they lack – even African pygmies and the Andamanese have the bow. And Central Asians possessing the gulak never abandoned the bow.

Deer can be hunted without weapons by chasing them to exhaustion followed by strangulation of the then-exhausted animal. No technology is needed to bring down cervids but the fact big game hunting cultures produce large numbers of lithic points rules out deer as the primary source of subsistence for the Gissar people.

What cultural evidence points to Gissar pastoralism? Zooarchaeological remains alone may suggest only stealing livestock – as you know, this always led to conflicts between hunting cultures and neighboring livestock breeders – or the obtaining of food by trade.

Ranov and his colleagues noticed a regular patterning in the accumulation of cultural remains in Tutkaul over time. Considering that no specialized hunting inventory was found and hunting lifestyle doesn’t typically follow strict seasonality, they concluded that Tutkaul people were pastoralists.

Well that makes sense but I understand the Tasmanians were migratory on a seasonal basis, right?

What’s your reference? Tasmanians are a good example of perishable and undifferentiated hunting toolkit (spears with fire-hardened tips, wooden clubs and throwing stones) but I don’t know anything about their migratory habits.

Mmm… it was just something I remembered. But bear in mind these were the kind of sources promoting incorrect information such as the Tassies not knowing how to make or use fire. Though they very obviously did, because Tasmanian fire use affected the ecosystem of their island.

What i remember is that they moved from site to site according to the seasons, particularly to exploit marine resources on a seasonal basis. I also understand the Tasmanians were essentially foragers – plant foods, marine resources (shellfish and nesting birds) and small game (wallabies). I’m guessing they got at least 40% of their food by hand skills, making them Collectors rather than Hunter-fishers and explaining their limited toolkit.

Though the Tutkaul people were not living near the sea, its surely worth considering that there might be (or have been) some other wild, seasonal food source to exploit there that might justify the effort of migration.