Journal of Human Genetics, advance online publication, 09/01/2016; doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.110

A Partial Nuclear Genome of the Jomons Who Lived 3000 Years Ago in Fukushima, Japan

Kanzawa-Kiriyama,Hideaki, Kirill Kryukov, Timothy A Jinam, Kazuyoshi Hosomichi, Aiko Saso, Gen Suwa, Shintaroh Ueda, Minoru Yoneda, Atsushi Tajima, Ken-ichi Shinoda, Ituro Inoue, and Naruya Saitou

The Jomon period of the Japanese Archipelago, characterized by cord-marked ‘jomon’ potteries, has yielded abundant human skeletal remains. However, the genetic origins of the Jomon people and their relationships with modern populations have not been clarified. We determined a total of 115 million base pair nuclear genome sequences from two Jomon individuals (male and female each) from the Sanganji Shell Mound (dated 3000 years before present) with the Jomon-characteristic mitochondrial DNA haplogroup N9b, and compared these nuclear genome sequences with those of worldwide populations. We found that the Jomon population lineage is best considered to have diverged before diversification of present-day East Eurasian populations, with no evidence of gene flow events between the Jomon and other continental populations. This suggests that the Sanganji Jomon people descended from an early phase of population dispersals in East Asia. We also estimated that the modern mainland Japanese inherited <20% of Jomon peoples’ genomes. Our findings, based on the first analysis of Jomon nuclear genome sequence data, firmly demonstrate that the modern mainland Japanese resulted from genetic admixture of the indigenous Jomon people and later migrants.

This paper is important as a first attempt at a whole-genome analysis of the ancient Jomon population. The majority ancestor of Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan, the ancient Jomon population is believed to have arrived in Japan some 17,000 years ago, i.e. slightly earlier than the accepted archaeological horizon of the peopling of the Americas. Kanzawa-Kiriyama et al. (2016) also concluded that

“all the results suggest a deep Jomon divergence within East Asia, close to the Native American split.”

Recent whole-genome analyses have revealed that Amerindians tend to shift away from East Asians in the direction of West Eurasians. This is typically interpreted as the consequence of an early admixture of ancient West Eurasians, or Ancient Northeast Asians (ANE) represented by the 24,000-year-old Mal’ta (MA-1) DNA, into the ancestors of Amerindians after the latter had separated from East Asians. No modern populations in East Asia show higher proximity to West Eurasians than Amerindians. If around 25,000 YBP, when Amerindians were presumably developing as a separate population, Northeast Asia was a region where admixture between West Eurasians and East Asians was common, then we would expect Jomon, who branched off from East Asians, around the same time to manifest such an admixed genetic profile as well. But the whole-genome data from Sanganji Shell Mound Jomon decisively rules out this possibility. D-stats (Fig. 6 in Kanzawa-Kiriyama et al. 2016) clearly shows that Jomon are genetically distinct from MA-1 and are most similar to other East Asians.

Moreover, while Jomon is most similar to modern Japanese (predictably so, considering that Jomon is known to have contributed genes to the modern Japanese gene pool), it’s most dissimilar (in a pool of Amerindians, Northeast Asians and Southeast Asians) from South American Surui.

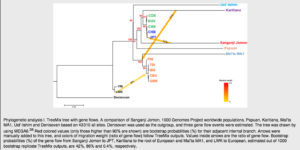

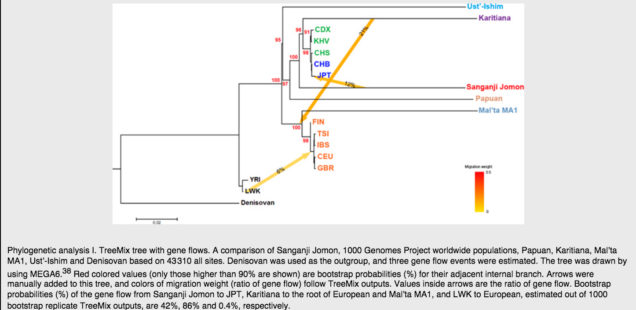

Unless we are willing to admit the action of divine providence that brought about the perfect timing and placement of the West Eurasian-into-Amerindians admixture event, which did not affect neither mainland East Asians nor the early, Jomon, branch thereof, it’s increasingly hard to believe in such a unique event. The facts become matter-of-course, however, if we postulate an early migration out-of-America into East Asia and, separately, into West Eurasia. This is precisely a scenario one would infer by looking at Kanzawa-Kiriyama et al.’s TreeMix run (Fig. 4,see below):

Not only is Karitiana forming an outgroup to the modern East Asian cluster, it’s also a source of origin for the gene flow into the base of the West Eurasian clade (including MA-1) – upstream from the Sanganji Jomon sample. The authors do caveat that this Karitiana-to-MA-1 admixture effect may be caused by their smaller library of SNPs (compared to other studies) and that a larger SNP library reverses the directionality of gene flow. (They also used Denisovan and not chimp as an outgroup.) But this larger library of SNPs also reverses the gene flow edge from Denisovans to Papuans, which is highly implausible. At the same time, their small library of SNPs correctly identifies gene flow from Jomon into Japanese. Even if the use of a maximally large collection of SNPs is methodologically rigorous, the question still remains: why do we find a signal of “West Eurasian admixture” all over the New World, ancient and modern, but nowhere in East Asia and not in ancient Jomon?

Dr. Carl Vincent, a retired professor and friend of mine, told me that he has handled pottery from American Mound Culture and Jomon pottery from Japan. He found them to be, not just similar, but identical. I have never been able to make sense of this, until I happened upon this web site. Good going!